The world is getting warmer. The “Greatest Snow on Earth” might be gone by the end of the century. Will Park City survive?

Part Two

Once upon a time, silver was the lifeblood of Park City. It flowed through the streets just as it flowed in rich veins through the mountain below. When the mining died out, Park City almost shared its fate. These days, our little mountain retreat relies just as much on a different resource—snow. Like the silver that came before, Park City snow attracts visitors from far and wide to these remote mountaintops beyond Salt Lake City. The local economy depends on these tourists, and the dollars they bring with them, in order to remain active, vibrant, and viable. What happens, then, when the snow goes away?

Paris and the Experts

Paris and the Experts

Despite the fervor of the public discourse surrounding whether or not climate change can be attributed to human activities, the globe is getting warmer. Leaders and activists from all over the world recently met in Paris to talk about the future of the planet, and our impact on this little blue marble we call home. Weather patterns are changing, and are projected to continue to do so well into the future. As a town that is near-wholly dependent on a specific meteorological phenomenon, one that is directly threatened by anthropogenic climate change, Park City is in a tenuous position. You can’t ski without snow. And the snow is going to be increasingly difficult to come by in the next few decades.

We sat down for a chat with two experts to find out more about the fate of Park City. We spoke with Brian McInerney, a hydrologist with the National Weather Service, and Bryn Carey, president of Ski Butlers, who has amassed a great deal of local expertise when it comes to the state of Utah’s slopes. Between their knowledge and experience, they helped us paint a picture of Park City in 2050. Unfortunately, it isn’t a pretty picture.

No More Snow

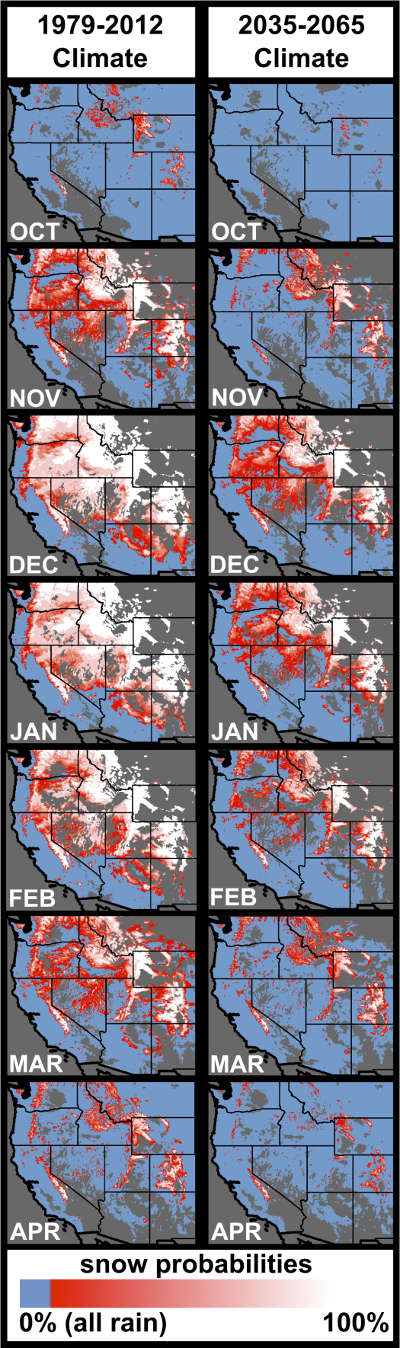

“The ski industry, in general, is going to go away,” McInerney said. “By 2035, snow cover will only be about 50 percent. In short, as global temperatures rise, snow is going to come later in the year. It will stick later, melt earlier.”

What used to be snow will end up being rain about half the time. Snow will move up the mountain, leaving the lower slopes devoid of “the greatest snow on Earth.” Sadly, the resorts can’t exactly pull up stakes and follow the snowline as it slowly creeps to higher altitudes. By the end of the century, there likely won’t be any snow at all in Park City.

We don’t have to wait until 2100 to see what is going to happen, though. Odds are, you’ve already seen it. If you have been around Park City in recent years, you have surely noticed the powdery white plumes that signal the round-the-clock operation of snow guns on the slopes. According to a 2012 study issued by the National Resources Defense Council, 88 percent of National Ski Areas Association resorts are using artificial snowmaking as a means to fill in the gaps that used to be covered by more robust snowfalls.

Can’t We Just Make More?

In fact, snowmaking seems like an ideal solution to the problem of lackluster winters, until you think about it. Making snow is hard. Making enough snow to cover a mountain to an acceptable depth for decent skiing? That’s even harder. Not only is it hard, it is expensive and inefficient. According to the same study, keeping the slopes white in order to keep the lights on costs a resort around $500,000 per season in electricity alone, not to mention the truly massive amount of water that diverts from agriculture, domestic use, and other applications. In the end, snowmaking is a solution that exacerbates the problem. All that electricity has to come from somewhere, and that somewhere is usually a fossil-fuel burning power plant that is making the very greenhouse gases that are causing the problem in the first place.

Gassed Out

While they are only a part of the bigger picture, greenhouse gases are a major factor in the rising temperature of planet Earth. A lot of our daily activity causes carbon emissions and other greenhouse gas release. I, myself, am at least partially responsible. So is everyone else who commutes to work. There are 1.2 billion cars on roads all over the world, each of which release an average of 4.7 metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year.

Sadly, all that commuting isn’t the only culprit. The larger share of residential CO2 emissions actually come during the winter as we all heat our homes. Our bedrooms aren’t the only places all that heating is going. It floats up to join the rest of the manmade mess cluttering up the air. And it isn’t going to go away. It is going to get worse.

Water Goes Down the Drain

There is more to the problem of climate change than simply increasing the temperature of the earth’s surface. That change in the mercury also governs the weather. As the temperature rises, precipitation will become more erratic. Right now, we depend on the annual snowpack to get us through the year. We don’t just ski on that snow. We end up drinking it, watering our crops with it, bathing in it, and more. That snow has to last from winter to winter to make human habitation possible in the otherwise arid stretches of the country. With a change in our climate, the water will come in less frequent, more intense bursts. It will get harder to hold onto. One only needs to look to drought-gripped California to see what happens when the water starts to disappear. The reservoirs will suffer for it, and so will we. If we go back to the snowmaking solution above, it gets even worse. We start using up that water pretending that everything is normal.

“We start using water to cover up the problem that using the water is making worse,” Carey offered, somewhat poetically.

The Dollars Dry Up

The Dollars Dry Up

So, we can’t just make more snow when the snow stops falling on its own. And we’re actively making it worse all the time. But what does that mean in terms of economic impact? We know the temperatures are going to climb, and that snow is going to disappear from the slopes of Park City. There will be an economic impact.

According to that NRDC study from earlier, Utah employed 12,964 individuals in the winter tourism industry during the 2009/2010 season. That counts people who work at resorts, ski shops, and the like. It doesn’t account for the restaurateurs, hoteliers, and others who rely on those other industries to stay afloat. The study estimates that, in that same season, Utah’s economy benefited from an additional $744 million as a result of that winter tourism. A different study, found via Park City Green, estimates that slumping snowfalls will claim about 1,200 jobs and $120 million in revenue from the Park City area by 2030, with 3,717 jobs and $392 million possibly disappearing by 2050. Unless locals find another way to rebrand Park City in the next decade, the town will probably have a repeat performance of its 1950s near-death experience only a century later.

Fighting Climate Change

“The grim reality is that we are warming,” McInerney said.

But is that really all there is to it? Is Park City doomed to die a slow, slushy death? It might certainly appear that way. The climate change models, the expert studies and forecasts, and the historical data clearly bear out a vision of the future that will leave the ski industry and Park City in the literal dust. But most of that assumes inaction. We assume that nothing can or will change. Sure, the end of the century may see Park City a decaying ghost town. On the other hand, we could get it together. We can fight for a future that includes fresh powder and white Christmases.

“We 100 percent have to fight for that,” Carey said.

We’ll be back next week to talk about what that fight will look like.

Leave a Reply