Here’s our look into the science of snow predictions: the methods, models, and limitations of ski season forecasts.

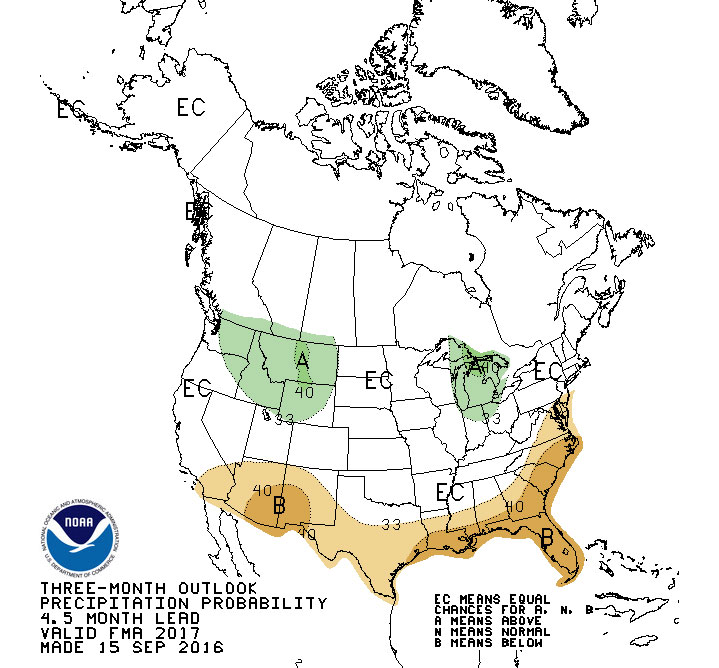

How are those forecasts created? How far ahead can they predict winter weather? How accurate are those predictions? Early 2016-2017 projections show a toss up, there are equal chances of an above-average or a below-average snowfall for Park City. As it turns out, weather-mongering is a difficult affair, full of more than a few surprises.

Skiing is an activity that lives and dies on snowfall. Powder underfoot is the ultimate measure that decides whether the slopes are open or closed. Manmade efforts to create or manage the depth of the snowpack exist, of course, but these are only expensive stopgaps designed to get resorts from one storm to the next, not replace Mother Nature’s wintry schedule.

With so much riding, both literally and figuratively, on the amount of snow on the ground, everyone wants to know how much to expect, and when. Booking a ski trip months in advance, allocating the resources to groom the slopes and clear the streets, setting the opening and closing dates for resorts that attract guests from all over the world—these are all difficult tasks that require the most up-to-date and accurate forecasts available to avoid costly mistakes.

Historical Data

Located at such a high altitude, Park City has always seen its fair share of the white stuff. Though Park City only saw 175 inches of snow over the 2015-2016, our little Wasatch community has averaged 411 inches of yearly snowfall over the last 30 years. That is nearly 35 feet, every year. That is a massive amount of fluffy, fantastic Utah snow, more than enough to support the excellent resorts that call Park City home.

That doesn’t mean everything is ideal. Not every year meets the average. As mentioned above, Park City only saw 175 inches last year. Even on good snow years, it isn’t falling in a neat, even distribution over every day of the winter. Some days it dumps two feet of powder on the slopes, some days are dry. The volume on the slopes fluctuates greatly from day to day based on recent precipitation, direct sun exposure, ambient temperature, wind conditions and more. Predicting perfect conditions is a difficult job that modern science is only really starting to manage with any reliability and distance.

The Difficulties

No one can really predict the weather accurately. That level of meteorological prognostication isn’t yet within the grasp of even our most sophisticated super computers. There’s plenty of reason for that, and most of it has to do with scale.

Weather is a global phenomenon, an immeasurably complex system of interrelated factors all working on each other on a planetary, even cosmic, basis. Solar position, ocean currents, intercontinental pressure systems, local geography and more interact on a constant basis, each input changing the results everywhere else, simultaneously. An observed front that meteorologists expect to continue in a predictable path might suddenly die out or veer off based on factors that predictive models failed to account for. The snow you were promised for this weekend in Utah might decide to become rain in Yucatan, Mexico instead, with little warning. The blue skies ahead could suddenly fill with 18 inches of snowfall, despite the assurances of the local weatherman.

Models and Aids

There are many ways to predict the weather. From cutting edge modern methods based on global real-time calculations, to rustic folk methods inspired by centuries of primitive attempts to understand the cycles of the natural world. They vary in range from just a few days to months in advance. Some are more accurate than others, and new methods are being created all the time as part of our effort to master the art of forecasting.

NOAA/NWS

Most weather forecasting that the average person sees gets its start at agencies like the NOAA, or National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the NWS, or National Weather Service. These groups are part of a worldwide network of dedicated meteorologists, physicists, mathematicians, statisticians, record keepers and more. They observe weather patterns all around the world using radar, satellites and other data-collecting hardware to catalogue the constant shift in environmental factors at thousands of sites all around the country and the globe. All that data is plugged into complex mathematical and physics models that predict upcoming activity based on historical patterns full of esoteric acronyms like ENSO, MJO and NAO (which stand for El Niño Southern Oscillation, Madden-Julian Oscillation and North Atlantic Oscillation, respectively).

These models come as close as we are yet capable to accurately describing impending meteorological behavior, especially over the next three days. Much further out, and the accuracy dives from 80 percent to no better than chance very quickly. The models simply can’t account for that much uncertainty. There is too much we cannot measure, and cannot calculate.

There are large gaps in our observational capabilities. Even our ability to map global topography within observed data points is spotty at best. Mountain ranges, for instance, are full of little rises and valleys, caves and rivers that affect the environment at the local weather. But within predictive models, they just appear as big, long lumps. Even using the most sophisticated computers on the planet, it would be too hard to account for all of that variance, and it has to be trimmed back to more abstract details in order to run the math and output usable results.

Even with these deficiencies, the wonders of modern meteorology are always advancing, giving us more accurate predictions further and further out. It was only in 2000 that standard forecasts moved from five to seven days out. In the next few decades, we could get a fairly accurate forecast up to a month out, or more!

Powder Buoy

While the formulas and models above were designed to provide an overall snapshot of potential incoming weather, there are more specific forecasts that some visitors to Park City might find more useful. There is one popular, somewhat unusual tool that one group uses to forecast Wasatch snowfall two weeks in advance.

Powder Buoy, as it is called, is a buoy floating in the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii, 3000 miles away from Park City. It predicts incoming storms by measuring the height of waves in the ocean, among other data. Low-pressure fronts, which signal incoming storms, cause the height of the waves to swell. Two weeks(ish) after the front passes the buoy, the storm appears in our neighborhood, bringing snow during the winter months. Powder hounds watch the data like hawks, eagerly scheduling their days on the slopes based on the seemingly prophetic output of this floating sentry.

Like all methods, Powder Buoy isn’t perfect. Measuring just one factor, low-pressure fronts near Hawaii, isn’t going to give a complete image of upcoming snowfall. But it is a pretty neat way to pick a likely date range. As usual, that front can fizzle out, run into a different system and divert, or do any number of other things the buoy is poorly equipped to communicate. It is worth checking out, even just as a novelty, as it does seem to nail at least a good number of predictions.

The Old Farmer’s Almanac

Thus far, we’ve talked about primarily modern means of divining the complex dance of the heavens. There are more antiquated, esoteric means of atmospheric augury that are still in use today. One of the most famous of these is the Old Farmer’s Almanac. Using formulas created in 1792 by Robert B. Thomas, this little book purports to be able to make long-range predictions regarding temperature, rainfall, snowpack and more.

Good Mr. Thomas believed that the earth’s weather is profoundly affected by sunspots, and that the study of solar activity would lead to fruitful projections when paired with the examination of historical trends. Claiming for themselves an 80 percent accuracy rating, the folks at Old Farmer’s Almanac give their predictions in the form of deviations from the 30-year historical average. Whether or not that claim of accuracy is to be believed relies on how much stock one places in the somewhat vague nature of the advice given. Some suggest that the almanac is little more than a meteorological fortune cookie, giving hazy advice that could accommodate nearly any actual occurrence, while others swear by its time-tested prognostications.

Folk Phenomena

As interesting as the Old Farmer’s Almanac is, there are even more bizarre folk means of predicting the weather. One idea presented as an infallible method of divining the state of the upcoming winter involves the study of the breastbone of a recently deceased local goose. The length of the breastbone correlates to the length of the impending winter—though it requires an understanding of the relative length of goose breastbones, so some practice may be required— and the amount of mottling on the bone shows the severity to be expected. The more mottled, the more snow. The number of snowfalls can also be obtained by counting the number of foggy mornings in August, or by counting back from the first snowfall of the season to the preceding new moon.

These are obviously very serious and scientific means of making weather forecasts, and can be augmented by other very important measures such as the general friskiness of cats in the fall, the extend to which rabbits are hiding in brush piles, and the depths to which squirrels bury their nuts. For the truly dedicated, there is an entire yearly measure of precipitation that can be taken every New Year’s Eve involving a dozen onions properly arranged in an east to west orientation, salt, and relative moisture. Take that, NOAA!

But Will it Snow?

As it turns out, there are tons of different ways to try to forecast the annual snowfall. But even with the most sophisticated tools in the modern arsenal, any attempt to make a long-range declaration amounts to little more than educated conjecture. In any case, you can always book a ski trip to Park City, knowing that we get some of the world’s most incredible powder every single year. The exact dates and volume may differ from year to year, but there will always be plenty of snow on the ground during the winter. So long as the resorts are open, there will be world-class skiing to enjoy in Park City.

While some Decembers may see low general levels of snow, there is always more than enough terrain for all but the most discerning skier. An early trip has the added benefit of some killer deals and packages, allowing you to save big bucks over a peak season stay. However, if you want some serious terrain to tackle, January or February tend to be the big snow months.

Leave a Reply